Tough Love

I was drying out in the Civic Hospital. It was back in the early 1980s during the AIDS scare, but long before the discovery of Hepatitis C in 1989. I was in an isolation room as a precaution. So much was unknown then.

My liver markers were all off: leucocytes, reticular counts, liver function tests and bilirubin. I was also quite jaundiced and tired. Things were catching up with me.

Lying alone in my single room in the middle of the day, I was surprised when Ma popped in unannounced. I hadn’t seen her for a while so it was a mystery as to how she knew I was there.

She was her usual kind and accepting self, offering encouraging words and faithful support. But I noticed she was rushed, her answers short, a tension just under the surface of her demeanour that I couldn’t quite grasp and put a reason to.

After a few minutes, she told me to take care and that she was leaving, mentioning my father was outside waiting to see me. Of course, she didn’t give me enough time to ask why he hadn’t come in. She said goodbye and hurried out of the room.

As my gaze followed her out, she swung open the heavy door with its tiny porthole window common to the isolation ward. There I could see my father in rumpled suit jacket and tie, purposefully pacing back and forth in the hallway. Before I could say anything, she was gone and in he came.

I tried to say hello but he cut me off. Coming closer, he spoke with just a hint of some ill-defined emotion, the kind you might see when you can’t tell if the person is hurt or angry. He said something like this to me: “Christopher, if you keep living the way you are, surely, you are going to die…and soon. When you do, we will gather together as a family and mourn your passing. It will be our last goodbye. Afterwards, we will bury you and then… we’ll forget you.”

With that, he turned and walked out.

Admittedly, he’d caught me off guard. I was stunned. I was in a hospital after all. What a jerk, I thought. As the door closed behind him, the pressure in me rose. I railed internally with questions, invectives; the cussing in my mind going off like fireworks.

He had left right away, so it wasn’t like I could argue with him, making it even more frustrating. How absolutely unfair of him, I decried to myself.

Outraged, in my mind’s eye I saw myself in my hospital nightgown, following him down the hallway, demanding, what exactly did he mean by that whole “forget you” bit? And who was HE to be speaking for all of MY brothers and sisters? There are eight of them; had he done a poll? Was this all based on their consensus? I wanted to call them and check for myself.

The scene revolved continuously through my mind as I lay there on my bed, him long gone. I must have stayed steaming for quite a while, fuming to myself over the images. Mumbling at times out loud that it was none of his business, damn it, how I chose to live my life. This was my problem, not anyone else’s.

But in time, I calmed down. I couldn’t stay agitated forever. Eventually, my anger subsided enough to return to a kind of normal. My breathing slowed, my thinking became more introspective. The scene was still fresh in my mind. I kept going over its details: the way he’d left me there by myself; the harshness of his judgment and the finality of its imagery. Suddenly, I felt alone, very alone… and saddened by it all.

I thought about my sisters and brothers. Childhood images flashed by, with them as freckle-faced kids on adventures we’d shared. I was so hurt; I felt a clear and justified self-pity. It was cruel to come into someone’s hospital room—a real medical patient with real medical issues—and say stupid stuff. Anyone would sympathize with how wrong it was.

I felt sad, lonely, and sorry for myself, resigned even. It was all so depressing. As if I didn’t have enough problems.

The more I thought about it, I remembered the way my mother acted during her short visit. She was clearly preoccupied. She had gone through the motions of visiting, but betrayed a hidden agenda. It was then I realized my mother had been in on it from the start. It was a damn set up!

The nerve of her to come in here with her “sweet as a lamb” approach and then help him pull off this kind of bullshit. She was a wolf in sheep’s clothing, that’s what she was!

Now I was mad again.

I could just imagine the two of them concocting their approach for maximum effect before arriving. “He’s in isolation?” he would have asked. She would have replied, “Yes, that’s what the others are telling me. Here’s the room number.”

Dad would have given marching orders: “You go in first; I’ll wait in the hallway. Don’t stay too long. I don’t want you making him feel any better.” She would have assented — like the devoted wife she was.

What a supreme jerk, I thought, envisioning how the whole scene played out in the car on the way over. The gig was up; I was on to them. That’s it, no more Mr. Nice Guy from me. They’re cut off!

After a while, having made that decision, I calmed down. My mind slowed its racing thoughts. My indignity had peaked and ebbed, like a tide of tension leaving shore for sea.

I felt alone again. Now, I was down. I felt it in my body, tired, sorry and sympathetic. It was sad, you see.

I imagined myself at a funeral, my own, watching all of my siblings mourn as they got ready to bury me. I could see my sisters crying in pain like they had when I’d been punished as a child — or like the time my father tossed me out of the house at age 15. I regretted I wouldn’t see them again, that I would have caused them pain. I was hurt, not for myself, but valiantly I thought, only for them.

That’s when I realized it was my father who was causing this anguish to befall my siblings. It was he who was making them turn their backs on me and to literally leave me in the dirt. It was he who was demanding once again the ultimate ostracism of one of his family members. Once more… what a jerk!

Now I was mad again.

The infinity loop

To be honest, I swung from one side of those emotions to the other for a long time after the incident at the hospital. I had no idea why; I guess I couldn’t see the forest for the trees. I lacked the resources to give me a deeper understanding of my father’s intentions. Neither could I see the basis of how I was reacting to his attempt at tough love; as an effort to shock me into seeing my life as it was.

If I tell you a good joke, you will hopefully laugh. After a minute or two, you will stop laughing as your brain normalizes whatever incongruence made you see the funny.

If you watch a sad movie, you may be so moved by its story and characters that you weep. Once your tears are discharged as pent up tension, your body will adjust, return to some kind of equilibrium and crying will stop.

This is the familiar homeostasis at work on your emotions, returning them to a balanced state. Laughing at a joke or crying over a sad scene in a movie are times where we suspend our own personal disbelief to get the full emotion—laughter or tears—of a situation. In our personal lives, it’s less easily managed simply because we have more at stake: our sense of self.

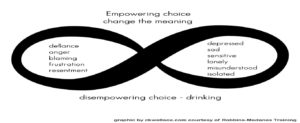

So picture an infinity sign with two opposites of emotion on each of its ends: frustration, blaming, anger, etc., on one side; sadness, self-pity, depression, etc., on the other.

Something happens to trigger us emotionally. Start anywhere in the loop; it depends on the person.

Let say at first we become frustrated, angry, blaming or even fall into a rage. You can’t remain that way forever so in time we return along the eight towards our feelings centre—our internal balance.

However, since whatever triggered us wasn’t resolved, the pain remains… and staying in the centre is temporary. Instead, we might continue on to the other side of the loop, moving from frustration, blaming and anger to experiencing sadness, self-pity, depression, etc. In turn, we can’t remain like that forever either. So at some point we return towards emotional neutral.

But again, since we weren’t able to resolve whatever it was that got us so upset, we think about it until we are angry again. This can go on for days, weeks, years even, where the cycle repeats over and over to exhaustion. Tony Robbins calls it the crazy 8.

It creates a tension inside us that craves relief, often an escape by whatever means necessary. Some go and get drunk; a way many choose to deal with emotionally charged events when lacking resources to respond in a more empowering way.

But it’s a never-ending loop, darn it. That’s why the infinity symbol is so appropriate: it goes on forever. The trick is to escape the infinity loop at the top, as opposed to exiting out the bottom. Taking the high road is the perfect metaphor, and it starts first with our own re-adjustment of the meaning we give things.

None of us is immune to the emotional swings of the Infinity Loop: attachment, fear, our expectations, shame and guilt, all of these conspire to put us under their emotional control. Where we differ is in how fast we can extricate ourselves from its cycle. That takes courage, honesty, acceptance, a fair bit of humility and forgiveness even; and often it takes space.

It’s all in the meaning

It took time, a few more years in fact, but eventually I resolved things in a way that gave me a deeper appreciation for what the old naval officer had been trying to do.

I realized it was my lifestyle that was causing others pain; but more importantly, I had no right to do that to people who loved me. Up to then, I might have thought it didn’t matter because I couldn’t acknowledge anyone cared. I had such a low opinion of myself that in my shame, I felt I had rights to self-pity, anger, and the dysfunctional life I lived. Perhaps I could let my guard down and see things by the light of a different day.

That minor shift allowed me to reconstruct the episode with more insight; in a way that to my mind gave us both back our dignity. I assigned new meaning to the hospital episode with my father based on a more profound perception of his intentions.

He wasn’t there to hurt me; he was there to protect himself and the others from the hurt I was causing by living so closely to destruction and death. It wasn’t malicious at all. In his clumsy way, it was an act of caring for his family. By extension, it was a desperate attempt to care for me too.

In the ensuing years after the hospital visit, I kept thinking of the old man and the way his lip quivered as he struggled to get the words out quickly so as to not lose the power of what he had to say. I’d overlooked the impact of that image in the aftermath of my reaction. But it was there; embedded in my subconscious as tiny flashes of recall, unavoidably part of the scene. All I had to do was focus on it.

He was in my hospital room, a deeply faulted man but still a naval commander and patriarch to a family of nine children—five of them grown sons—trying his best to be tough when it was obvious by the look on his face his heart was breaking. That’s the image’s meaning that has stayed with me.

His love wasn’t so tough; it was just plain love.

Stay Powerful,

Christopher K Wallace

©2015 all rights reserved

https://advisortomen.com/board-of-directors/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/advisortomen